Views

PROFESSOR GORAN MAKSIMOVIĆ, PHD, ABOUT LITERATURE THAT MAKES US BETTER AND STRONGER

Cautionary Study of Memory

Where memory failed, we found crisis or loss of identity. It is no coincidence that conquest ideologies were based on the denial of memory, just like contemporary colonialism. Besides the official, there is an entire history of forgotten Serbian literature and culture. Only when we unite them, we will see how rich and heterogenous Serbian language literature is. Experiencing Serbian cultural and spiritual space as a unique whole is a natural state of consciousness. Only essentially freedom-loving nations have the strength to laugh, both to others and to themselves, which is very clearly shown in the case of Serbia

By: Vesna Kapor

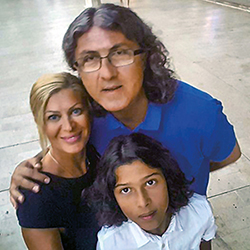

Photo: Personal Archive

He is professor of XVIII and XIX century Serbian literature at the University of Niš Faculty of Philosophy. Literature historian, anthologist, literary critic, lecturer at many Serbian and foreign universities, author of important studies about types of laughter in Serbian literature, about identity and memory, forgotten writers and chapters of Serbian culture…

He is professor of XVIII and XIX century Serbian literature at the University of Niš Faculty of Philosophy. Literature historian, anthologist, literary critic, lecturer at many Serbian and foreign universities, author of important studies about types of laughter in Serbian literature, about identity and memory, forgotten writers and chapters of Serbian culture…

Goran Maksimović (Foča, 1963) in an exclusive interview for National Review.

In this era, when wars are (also) led with narratives and for narratives, in this planetary triumph of banality and psychology of masses, what is happening with literature, its achievements and powers?

Nothing has essentially changed, except for the appearance of new technologies and terminologies, as well as new forms of propaganda manipulations. After the destruction of the ”block” world, great dust began swirling, blurred the essence of things, so ordinary man often could not find his way or became entirely disoriented in the contemporary moment. Liberal ”democracy” is today collapsing before our eyes, initiating great chaos, even stronger than in previous decades, when different generations frivolously believed its masked, yet essentially ultimately perfidious and sinister intentions. In all that, literature was often misused and pulled into various hideous ideologies. Despite everything, I believe in the original power of literature. Both in the past and in the present, literature has always had and will always have the same valuable mission to make the world a better and more beautiful place for living, and to encourage man to search for esthetic and ethic pleasures, thereby searching for the best in his being, for goodness and love. Those who reach those two greatest ideals of literature and art in general will find their way much more easily in all misfortunes of the contemporary world, they will be able to easily differentiate truth from lies, good from evil, philanthropy from selfishness and hypocrisy.

Where has the ”road of Serbian literature” (as Professor Jovan Deretić, PhD, your mentor at the Faculty of Philology, calls it in the title of his book) brought us? Does ”Serbian literary individuality” exist today and (if it does exist) does it contribute to ”preserving national identity”?

Where has the ”road of Serbian literature” (as Professor Jovan Deretić, PhD, your mentor at the Faculty of Philology, calls it in the title of his book) brought us? Does ”Serbian literary individuality” exist today and (if it does exist) does it contribute to ”preserving national identity”?

Any memory of professor Deretić lights me up. He is one of the greatest historians of Serbian literature. His masterly interpretations and far-reaching literary and historical syntheses are impressive. He was a man who carried goodness and selflessness within himself in an authentic manner, while very hard work and extraordinary knowledge of literature made him a scientist whom we could trust without reserve. I consider myself privileged for having had the opportunity to work with him. The road of Serbian literature, which he brilliantly described, is extraordinary for the unbreakable and creative permeation of the individual and collective principle, while the size of Serbian literature is contained exactly in the kind of artistic excellence which, at the same time, preserved individual and national identity. In the greatest works, in the greatest writers, in the magistral streams of Serbian literature, those two sides of one identity have never been challenged.

SUPPRESSED HISTORY OF SERBIAN CULTURE

In your study Identity and Memory, you deal with ”forgotten writers and marginalized works of Serbian literature”. Who are we forgetting and why, what is being removed from our eyesight, with what intentions and consequences?

In your study Identity and Memory, you deal with ”forgotten writers and marginalized works of Serbian literature”. Who are we forgetting and why, what is being removed from our eyesight, with what intentions and consequences?

The basic idea of my book has just been expressed in the cover syntagm. When memory failed, we had a crisis or loss of identity. It is no coincidence that conquest ideologies were founded on the thesis of denying memory. Contemporary colonialism has again pulled out the old phrase that we need to forget the past, in order to watch into the future. However, historical experience, as well as the entire artistic experience, before all literary, tells us the opposite: if we want to perceive the future in the right way, we must cherish memory and preserve identity. Researching forgotten writers and works of Serbian literature is based on actual ”studies of memory” and remind us how much we can be impoverished in terms of spirit, esthetics and identity, because of forgetting or suppressing important individuals, acts or events from the past. Reasons for such oblivion are different. There is much truth in the interpretation that the Serbian nation is prone to easily neglecting the past. Sometimes oblivion is ideologically conditioned and provoked on purpose. Sometimes it is just in artistic reasons and disagreement in the horizon of artistic expectations of new generations of readers. Independently from everything said, the truth is in the following. Besides the official history of Serbian literature, there is an entire history of forgotten Serbian literature and culture. The task of new generations of researchers, among others, should be in uniting the two histories of Serbian literature. Only then we will see how rich and diverse literature written in Serbian language is.

You teach XVIII and XIX century Serbian literature, but you also follow contemporary literature. What is the relationship between the past, or literature of that period, and contemporary literature?

You teach XVIII and XIX century Serbian literature, but you also follow contemporary literature. What is the relationship between the past, or literature of that period, and contemporary literature?

Most part of my research focus is on Serbian XVIII and XIX, as well as early XX century. I follow contemporary literature mostly from curiosity and the need of esthetic entertainment. It gave me a non-binding and unburdening role to choose books I will write about. Although I published more than 150 literary criticisms, we could still say that I wrote about contemporary books as a literary historian. Most of my works are about contemporary books and writers in which I recognized echoes and voices, poetic ideas, and enthusiasms of previous époques, mostly Serbian XVIII and XIX century. I don’t know how successful I was in it, but I do know how nicely refreshing such writing was for me and that, after it, I returned to researching writers and works of previous centuries with more passion.

AWARENESS OF ALL-SERBIAN UNITY

You were born in Foča, studied in Sarajevo and Belgrade, you teach and publish in Niš, Banjaluka, and elsewhere in Serbian lands. Is there a Serbian cultural space and cultural expression of awareness of a whole?

You were born in Foča, studied in Sarajevo and Belgrade, you teach and publish in Niš, Banjaluka, and elsewhere in Serbian lands. Is there a Serbian cultural space and cultural expression of awareness of a whole?

It is important to underline that I graduated my basic studies at the Faculty of Philosophy in Sarajevo (1983–1987), and that I had an opportunity to learn from excellent literature professors and, above all, good people. I will mention, with great respect, the names of Branko Milanović, Ljubomir Zuković, Radovan Vučković, Branko Letić, Milica Ivanišević… I came to Belgrade for my postgraduate studies, and later defended my master and doctoral theses, as I have already mentioned, with Professor Jovan Deretić.

I attended a high-level gymnasium in Foča. It established my deep educational foundations and excellent discipline, which have been following me to the very day. I deeply believe that anyone who grew up in this picturesque environment on the banks of the Drina has a strongly founded patriotic awareness. Thanks to it, I matured as someone whose views of the united Serbian cultural and spiritual space have always been a natural state of awareness. I have always experienced and felt the literature of the Serbian nation and Serbian language as a part of an unbreakable whole. Entirely in the spirit of Šantić’s anthological verses: ”And wherever there is a Serbian soul, // is my homeland, // My home and my native hearth”. Niš is my new homeland, and, above everything, the city of birth of my son Nikola, so I experience it with additional emotions and duties. I am sure that, as long as Serbian language and Serbian literature exist, the untied Serbian cultural space will exist as well.

The subject of your doctoral thesis was ”Types of Laughter in Serbian XIX Century Art Prose”. You published essays about Sremac’s laughter, Domanović’s and Triumph of Laughter (2003). What is Serbian laughter like, and can it be used as means of self-defense?

The subject of your doctoral thesis was ”Types of Laughter in Serbian XIX Century Art Prose”. You published essays about Sremac’s laughter, Domanović’s and Triumph of Laughter (2003). What is Serbian laughter like, and can it be used as means of self-defense?

Researching the phenomenon of comedy in literature is my biggest and certainly most joyful scientific passion. I am thankful to Professor Deretić because, as my mentor, he supported my intention to research this artistic phenomenon in the corpus of Serbian XVIII and XIX century literature. Comedy is based on everyday things in life and the experience of comedy is manifested through three dominant forms of laughter: humor, satire and parody. Only free nations and those who constantly fight for all kinds of forms of freedom have the strength to laugh, both to others and to themselves. That is the greatness of any nation, including Serbian. My research of comedy and laughter was mostly directed to writers and works from the XVIII и XIX, and partly the XX century, through the works of Nušić, Ćopić, Kulenović and Kovačević. Serbian literature is an inexhaustible treasury of comic genres. I researched different forms of laughter in Serbian literature, from Dositej Obradović, Sterija Popović, Kosta Trifković, Sremac, Matavulj, Domanović, Nušić, to Ćopić, Skender Kulenović and Dušan Kovačević. Serbian laughter appears in different forms, from benign humor, caustic satirical ridicule, to grotesque experiences which unite both comical and tragical feelings. There is a thin, sensitive line between comical recognition and tragic catharsis, which can be recognized and depicted only by true masters of narration or comedy plots. Humoristic joyful laughter is often permeated with melancholy, which is a feature of Sremac’s laughter, while satirical ridicule is often permeated with self-irony, which is a feature of Domanović’s laughter. Humoristic laughter and satirical ridicule appear in Sterija’s and Nušić’s comedies in inseparable unity, as well as the comic and tragic feeling of the world, which constantly warns us that we must be better and more sincere both to ourselves and to others.

IDENTITY ENGINEERING, BETWEEN COMIC AND TRAGIC

You have edited anthologies of Serbian XIX and XX century love poetry. Are we still able to sing about love and what has changed in that sense compared to the period included in your anthologies?

You have edited anthologies of Serbian XIX and XX century love poetry. Are we still able to sing about love and what has changed in that sense compared to the period included in your anthologies?

To my surprise, careful research led me to the knowledge that Serbian poets are still successfully writing love poetry. It’s not just the XIX century, especially the romanticism epoque, that created great love lyrics. Besides incomparable Branko Radičević, Zmaj, Đura Jakšić and Laza Kostić, the modern epoque created great love poets as well: Šantić, Dučić, Rakić, Dis, Pandurović, as well as the entire XX century, from the poetry of Miloš Crnjanski, Nastasijević, Rastko Petrović, Vasko Popa, Branko Miljković, Stevan Raičković, to contemporary lyricists: Matija Bećković, Tanja Kragujević, Radmila Lazić, Zoran Kostić, Radoslav Stojanović and others. In the XIX century, love lyrics was growing in the symbiosis of strong and utterly sincere emotions, bohemian mood and tragic visions of ”the dead sweetheart”, while in the XX century, the feeling of love was permeated with strong erotic passions, psychological self-analyses, pretentious experiences and alike. There are many young poets today, who write remarkable and powerful love poems. Although I could name so many of them, I will just mention a few – Milan Gajić and Zorica Penić.

You believe that ”our battle for preserving Serbian language, therefore also the Cyrillic alphabet, must be the basis for preserving our national consciousness and identity”. How should we lead that ”continuous battle” today?

You believe that ”our battle for preserving Serbian language, therefore also the Cyrillic alphabet, must be the basis for preserving our national consciousness and identity”. How should we lead that ”continuous battle” today?

This is not the first time we are exposed to such a battle for defending Serbian language and Cyrillic alphabet, as the original Serbian alphabet. If we, perhaps, remember the Austro-Hungarian ”Kallay politics” in occupied Bosnia and Herzegovina in late XIX and early XX century, everything will be obvious and clear. A similar thing was happening in occupied Serbia in World War I. All attempts to destroy Serbian identity were based on similar projects. We should also add the strategy of destroying Serbian Orthodox Church, as well as the attempts to forcedly rename it or confiscate its property. Our fathers experienced something similar in Macedonia at the time of socialist Yugoslavia, so the remaining Serbs in that small state do not have the freedom of confessing their faith. We have seen it before our eyes in forcedly deserbianized Montenegro, and it was stopped by organized processions and strong resistance of Serbian people. The battle is very far from its end and it will probably come to life again in a new criminalized and auto-chauvinist form. New colonialism and renewed geopolitical strategies in the Balkans have actualized the battle for destroying Serbian language and alphabet. In the past, most of those battles failed or were postponed for a more convenient time, but they always left serious consequences. That is why it happened that we have a number of political languages derived from the Serbian linguistic system. Examples of the so-called ”Montenegrin” and so-called ”Bosnian” language are best indicators how senseless and comical those concepts of ”linguistic engineering” are, but, at the same time, ultimately dangerous for the survival of the Serbian nation.

OVERPOWERING DENATIONALIZATION STRATEGIES

There is almost not a single family that does not remember the martyr and heroic narrative in its legends, however, when speaking about the media and the cultural scene, we have a dominant parvenu spirit: anything not local is excellent. How did we get here?

There is almost not a single family that does not remember the martyr and heroic narrative in its legends, however, when speaking about the media and the cultural scene, we have a dominant parvenu spirit: anything not local is excellent. How did we get here?

The family culture of memory is what essentially saves the identity of any nation, including Serbian. As long as we teach our children what our ancestors sacrificed to gain freedom, which we so easily deny today, there is real hope in preserving our identity. The parvenu spirit of denationalization is an old problem of the Serbian nation. Sterija and Zmaj, Trifković, Laza Kostić, Nušić and many others have written about it. How did we come to that again? Through well-designed strategies of denationalization and destroying identity. Unfortunate communism and self-managing socialism have done much harm to the Serbian nation; they consumed its identity and built up the feeling of guilt for invented ”hegemonism”, initiated the irrational ”self-hatred” and created systemic Serbophobia in others, especially the most recently created Sothern Slavic political nations, which are ethnically related to the Serbian nation or derived from it. It will take much will and strength to overcome all that. The fact that the original national spirit has always conquered the parvenu or ideologically imposed spirit of denationalization is comforting. I want to believe that the same will happen in our era, as well as in the future.

You work in high education with young people. What happened with the Serbian educational system and can we rely on it today?

You work in high education with young people. What happened with the Serbian educational system and can we rely on it today?

Right at the beginning, I will underline an undeniable truth. Most of our students are the best part of our universities. I want to distance myself from individuals and minor groups of students, political manipulators, who are, upon someone’s order, misusing the sublime idea of education and autonomy of the university. There is, of course, a decent number of self-aware teachers, who know well the problems of contemporary high education and what it will face in the following years if such a negative approach continues. For twenty years, high education, as well as all other levels of education, have been exposed to systematic destruction. It was achieved through the so-called ”Bologna Concept” strategy, based on the insane idea about financial self-sustainability of study programs. The stated pressures at Serbian universities pointed towards two directions. The first was reducing studying contents under the excuse that they are too voluminous and don’t fit the European structure of transferring points (ESPB), thereby inevitably and entirely demolishing educational criteria. The second was related to the destruction of departments and faculties with study programs in terms of staff, bringing weaker teachers, so that the dead-born ”liberal” educational strategy could be achieved more easily.

Countries that preserved at least a bit of their state and national dignity and cared about maintaining their high education system have entirely rejected the Bologna concept or adapted it in a way to keep the ”Humboldt idea of knowledge”. The exact opposite happened at Serbian universities; we rushed to implement the reform as soon as possible, all spiced up with uncontrolled and entirely unbased establishing of private universities, which demolished educational criteria. All that pulled down state universities as well, so we came to what we have today, a serious degradation of high education.

At the same time, the ”science destruction” syndrome developed as well, through the procedure of so-called ”quantitative expression of scientific research results”. The procedure of quantification made serious scientific research senseless and turned researchers into zealous collectors of scientific points. We can see it in the fact that we can collect more points by publishing a single ten-pages work in a better ranked scientific magazine than by writing a supreme quality several hundred pages long scientific monograph, result of a serious research that lasted several years. Thorough, large scientific research, scientific synthesis, and monograph-type scientific proof, which move forward knowledge in certain scientific areas, are cast aside and made meaningless, while small texts, articles and small research are encouraged, in which, even if you wanted to, you cannot achieve serious scientific knowledge and conclusions.

Due to all this, it will take much will and strength to recuperate high education. I believe in the vitality of young generations, in the historically proved self-awareness of the Serbian nation, therefore the inevitable victory of genuine educational and scientific values.

***

Universities

Goran Maksimović (Foča, 1963) graduated literature in 1987 at the Faculty of Philosophy in Sarajevo. He completed postgraduate studies (1993), defended his master thesis (”Branislav Nušić as Storyteller”) and doctoral thesis (”Types of Laughter in Serbian XIX Century Art Prose”, 1997). He began his university career in 1989 at the Faculty of Philosophy in Niš, where he has been regular professor since 2008. He was also chief of the Serbian Literature Cathedra (2000–2002), vice dean and editor in chief of the publishing activity (2002–2004), dean (2010–2016)... Since 2014, he has been chief of the Department of Language and Literature at the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts Center of Scientific Research and University in Niš. He held lectures at universities in Serbian Sarajevo, Prague, Novi Sad, Banjaluka, Timisoara, Kragujevac… He worked at universities in Aras and Poitiers (France), Maribor (Slovenia), Veliko Trnovo and Sofia (Bulgaria), Belgorod, Moscow and Kemerovo (Russia), Bucharest and Timisoara (Romania).

***

Books

Goran Maksimović published a series of studies in Serbian literature: Branislav Nušić’s Art of Narration (1995), The Magic of Sremac’s Laughter (1998), Domanović’s Laughter (2000), Serbian Literary Subjects (2002), Triumph of Laughter, Comedy in Serbian Art Prose from Dositej Obradović to Petar Kočić (2003), Critical Principle (2005), World and Story of Petar Kočić (2005), Experience and Sensation (2007), Comedy Orpheus and other Essays (2010), Identity and Memory (2011), Critical Feast (2012), Forgotten Writers (2013), Storytelling of the City and other Essays (2014), Simo Matavulj and Bay of Kotor (2018)... He composed anthologies: I Can Still Love. Collection of Serbian XIX and XX Century Love Lyrics (2002), Anthology of Storytellers from Niš (2002), Never Has Your Slim Body. Anthology of Serbian Romanticism Love Lyrics (2005)... He edited about forty editions of Serbian XIX and XX century writers...